First-Generation College Students: Your Mental Health Matters

By Breanna Georges

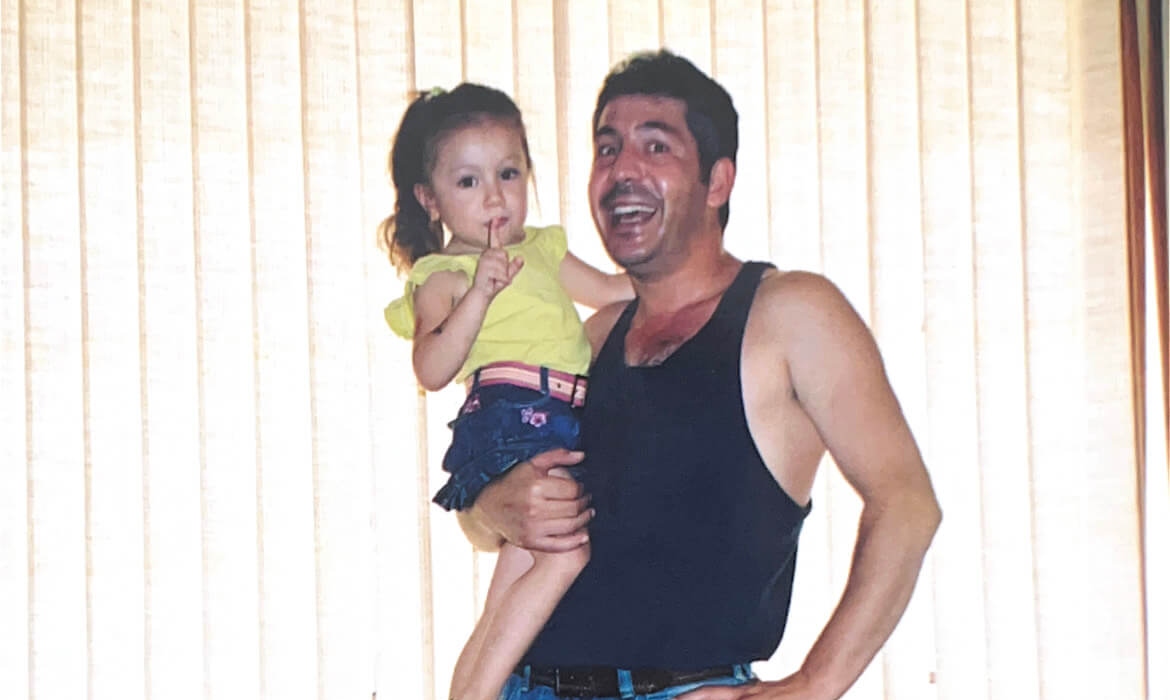

I am in my fourth year of college and about to start grad school, and I have been in eating disorder recovery for the past two years. I have learned a lot from my lived experiences as a queer, BIPOC woman and child of immigrants who struggled with mental health—especially in college. A big part of my identity is being a first-generation student, which refers to the children of immigrants who are the first in their families to receive education in America, so I want to share the lessons I’ve learned with the hope that any first-gen student who needs mental health support and empathy can benefit from my story.

Like many first-generation immigrants, I often felt cut off from American society and culture, especially at school. Being raised in two different cultures—my father is Syrian and my mother is from Venezuela—was and continues to be both beautiful and challenging. My earliest memories involve feeling disconnected from my peers in elementary school. I grew up in a predominantly white suburban town, and my first language was Spanish. Learning to read and write in English was the first time I remember feeling the immense pressure to succeed. But that pressure fueled me, and I caught up. By age 6, I was in my school’s gifted and talented program, reading well above my grade level. That initial sense of academic achievement and validation was crucial in the development of my self-image.

So was being a child of immigrant parents. Above all else, I wanted to prove myself worthy of their immense sacrifices. Even though cultural divisions persisted, because of my mixed race and culture, I wanted nothing more than to fit in and assimilate.

To achieve all those goals, I decided to dedicate every part of my life to academic success, in hopes of proving myself not only to my family, but also to everyone around me. As I got older, my internal pressure to succeed grew heavier and heavier.

And I began to crumble.

Many sleepless nights studying, tears shed over not feeling good enough, and the immense burden of feeling that if I didn’t succeed academically I would be failing my parents, my family, and my culture led to panic attacks starting at 8 years old.

In middle school, a doctor referred me to a therapist to be screened for anxiety and depression. My mother didn’t agree. I was too young for therapy, she thought, and I could fix any negative emotions I was feeling by distracting myself with things that were more important, like school.

I listened to her.

I continued to prioritize my education above my mental health. Unlike what my mother thought, however, my stress did not go away. It found a way out through an extremely unhealthy relationship with food. With the help of therapy, building a support system, and really working to unlearn my cultural expectations, I realized how the pressure and anxiety I was dealing with were unique to my first-generation experience. I now understand that the expectations I was trying to live up to were not worth losing myself for. My eating disorder recovery has taught me about the importance of self-care, and I want to share some of what I’ve learned with the hope that whatever burdens you may be facing as a first-generation student are lifted—even just a little.

Take Time for Yourself When You Need It

In my experience, one of the biggest challenges for first-generation college students is that we often prioritize academic success at the expense of other things, making it easy to burn out. Taking care of yourself won’t solve all those problems, but it will help you slow down, center yourself, and know when you need support. Here are a few ideas:

- Practice meditation and breathing exercises.

- Take a class at school about immigration or your culture or background.

- Make a playlist of music you love.

- Incorporate journaling into your daily routine.

- Spend time with friends and family when you can.

- Listen to your body: Stay hydrated and eat when you’re hungry.

- Look for first-generation resources on campus or create your own if there aren’t any.

- Research counseling services available on campus.

Your Culture Is Beautiful and Worthy

BIPOC, queer, first-gen—all these labels apply to me, but none of them are the sum of me. My story is full of beauty and nuance. There is so much power and resilience to be found in your identity, despite systemic or socio-cultural barriers you may face. You hold the stories and experiences of all who came before you—the struggles, the laughter, the tears, the joy.

Previous generations live within us, and we have the power to grow from everything they have given us. Learn or research your culture and history independently, and value the time you spend with your family as honoring your background. There is so much beauty in all our respective cultures and communities. Without us, the world would be boring! Never let anyone take that away from you, and know you are not alone.

Education Is Important, But So Are You

My family has placed great importance on the value of education, and many first-gen students I’ve befriended have said the same. We learn from a young age that our path to success and all our dreams can be achieved only by excelling academically and getting a college degree. I appreciate how that mindset instilled hard work and dedication in me, but I am always trying to unburden myself from the constant yearning to succeed academically and professionally.

It’s not easy, but if we do it together—if we collectively push back on these generational values—we can create a new narrative for ourselves and the next generation.

One thing I’ve learned while recovering from my eating disorder is that nothing is more important than my mental health. How can you accomplish your goals if your emotional health isn’t taken care of? You can value your education while also honoring your mental health needs as a college student. In fact, valuing your mental health is valuing your education.

You Deserve to Get Help and Take Up Space

One of the most important pieces of advice I received from a professor was the importance of taking up space, especially for marginalized people. It’s incredibly important to be vocal and take up space wherever you are, within your own limits and with consideration for your safety and well-being.

Taking up space looks different for everyone, but when it comes to mental health, reaching out for professional help or even opening up to someone you trust are important ways to take up space.

Most colleges offer counseling services for students, which I used as a first step in my eating disorder recovery. I spoke to a counselor once a week until I was referred to different therapists and recovery programs, which is how I found the wonderful therapist I see to this day.

Remember: Your existence is incredibly valuable and important, and you have every right to seek well-being and know you are not alone when you do. We’re in this together. There is community and solidarity here for you as we all grow together.

Learn More About Managing Mental Health and Eating Disorder Recovery in College

Planning for Mental Health Challenges on Campus

Finding Mental Health Help as a College Student

Maintaining Treatment for Eating Disorders in College

Planning for College While Recovering From an Eating Disorder